Haunted Attractions with your Other Father by Norman Prentiss is the sequel to his Odd Adventures with your Other Father, and continues the horror/fantasy road trip adventures of Jack and Shawn as they fight monsters and homophobia in the ’80s. Cemetery Dance is proud to publish this new novel (with an e-book version now on sale at Amazon for 0.99!), and to celebrate we’re serializing a new novella featuring the characters from the books!

When we last saw Jack and Shawn, they joined another couple on a “Dinosaur Safari” tour, their guide Troy leading them downriver. After a (real? fake?) dinosaur sailed beneath their raft, nearly capsizing it, a massive whirlpool threatened to pull them underwater. They escaped, only to find themselves on a strange beach…

THE CANYON OF TERRIBLE LIZARDS, PART 5

(A HAUNTED ATTRACTION WITH YOUR OTHER FATHER)

BY NORMAN PRENTISS

Troy was no longer at the helm. At some point he’d peeled off his damp shirt, and now stood waist deep in water, his bare torso straining as he pulled our raft towards the nearby shore.

The water was calm and clear.

Behind us, the other couple murmured complaints about the rough ride, as if we’d simply been on a plane that suffered a bout of turbulence.

I lifted my head and noticed that the two of them were sitting up. Meanwhile, I was still sprawled ungracefully over Jack.

“Lemme up, will ya?” he said, and I tried not to shake the raft too much as I teetered into a seated position.

Jack made a strange non-verbal sound, a cross between a harrumph and an ahem, which I guess expressed the awkwardness of the situation. Though it might have been a coded compliment to our newly shirtless guide.

Troy leaned back as he neared the shore, his heels digging in, and the front edge of the raft brushed against land.

“Guess that’s our cue to get out,” the guy behind us said, followed by a shifting of weight in the raft, then a splash. Kenneth held his hands out for his girlfriend to follow.

Jack didn’t need any help. In his most graceful move of the day, he rolled out of the raft and waded to dry land in two long-legged strides.

Our guide kept pulling the raft, and I could swear he almost gave it a twist to hurry me out of it. I half-stumbled, then joined the rest of our group on shore.

“Nice little cove here.” Ken removed his camera from the Ziplock bag and snapped a quick picture.

“Never seen it before,” Troy said. “And I know this region like the back of my hand.” He pulled the raft fully from the water, dragged it along the small crescent of sandy beach and wedged it tight between a tree and a smooth-sided boulder.

“It’s part of the tour,” Kenneth said, reassuring his girlfriend. “It has to be.”

Troy didn’t respond. He shouldn’t have needed to. Each blink of my eye registered new, impossible details. The strange rusty color to the sand and sky; the thick-trunked trees with heavy, fan-shaped leaves. The rising wall of rock that formed a barrier beyond our small inlet, with a similar cliff-wall on the other side of the stream we’d just exited.

The Pterodactyl gliding across the sky overhead.

#

“That’s a kite.” Kenneth turned to our guide. “Don’t think we haven’t seen you pushing those buttons and making things move and roar.”

“He’s nowhere near the buttons.” His girlfriend stared at the sky in awe, although the flying dinosaur had drifted out of view beyond the cliff edge. A low throated squawk sounded in its passing, creating a strange echo in our secluded cove.

“It’s on a wire,” her boyfriend persisted, “and some kind of signal lets it loose.” He held his arms out straight, like he was playing airplane. “Then it floats in a straight line, slow enough so we all have time to notice it.”

Barb looked around, rather than crediting his explanation. He’d made a reasonable guess, considering the other fake things we’d encountered on our journey — the chiseled footprint, and the dino busts coated with cracked paint — but we’d clearly slipped off the pre-determined path of our low-rent tour. She was beginning to grasp the possibility now, her eyes wide, head turning to take in the surroundings, ears perked for any new, fantastical sounds of a forgotten world.

In her expression, I saw a child’s wonderous gaze of expectation, an openness to the impossible, an eager thirst for new experience. These are the moments we live for when travelling, and I envied her. I’d dwelled in skepticism, drifted into worry for Jack’s sake, then had plummeted into fear when our raft got tossed through raging waters. Now that we were safe on land, I should follow Barb’s example and enjoy the magic of the moment. Her jaw dropped, her eyes opened even wider. The best comparison I can make is when kids gets really excited, and they pump their arms and actually jump up and down in place, because they can’t wait to see what happens next.

“There’s no goddamned wire!”

(Oh. I’d completely misread her. She was actually building up to a tantrum.)

“I can tell the difference between a kite and something that’s alive, Kenneth. If. You. Think. That this piece of crap tour could come up with something that real, then you’re dumber than a box of prehistoric rocks. Does this feel like Arizona to you, Kenneth? Remember how a giant, tentacled fish attacked our raft, we spun around like a turd in a giant toilet bowl, and somehow we got flushed here into this canyon that’s nothing like the scenery we floated past earlier, the sky above us red like I’ve never seen, and these trees and these rocks like something from another planet, and that smell, I swear to Christ it’s like dust and sweat and raw meat, and the air’s half-choking me, and you’re telling me it was a kite? I saw its goddamn wings flap, you stupid ass. They flapped.”

(She kept going, Celia, and she might have dropped in some stronger curse words along the way. I couldn’t even look at her boyfriend, she was burning him so bad. Jack and I did that silent shared glance couples do sometimes, sort of a Boy, she’s really giving it to him smirk, with a hint of We’d never carry on like this in public, would we?

The nice part about Jack’s wry half-smile, though, is that it confirmed he’d mostly recovered from the trauma of our water-ride. We were back to normal, even if the world around us was not.)

“Let’s go on the dinosaur tour.” She deepened her voice here, adding an artful bit of strut-in-place to complete the imitation of her boyfriend. “It’ll be an adventure we can tell everybody about back home.” Then, dropping the caricature and resuming the full-throated diatribe: “Well, maybe we don’t effing get home, but at least we got to shit-swirl down the toilet time machine. And we were lucky enough to see a kite, a goddamn kite, before some gator-jawed monster crashed through the trees and ate—“

“Quiet,” her boyfriend said, and I winced, knowing full well how that tactic usually worked. A gentle Honey, you’re kind of losing it in public reminder usually has the exact opposite effect than intended, making hackles rise — and voices. As I’ve since learned, it’s the same reason librarians no longer bother to shush their noisy patrons.

Yet the tactic actually worked this time. Not because she realized she should take a few deep breaths and calm down, but because she noticed something new in her boyfriend’s expression. She could tell that he’d abandoned his wire-and-kite theory, and now agreed with her panicked assessment.

“The cliff,” he said. “Half way up.”

We all followed the angle of his outstretched arm to see where he pointed. A large section of protruding ledge seemed precariously balanced, ready to snap and tumble down at the slightest gust of wind.

She turned back to him, almost ready to resume her attack, but she kept her comments to a whisper. “Kenneth, I’m not going to start an avalanche, okay? I’m not going to break rocks with my—“

“It’s not a rock,” Jack said, being the first of us to dare enter the couple’s dispute. “It moves.”

“It blinks,” Kenneth said.

I didn’t see any blink, not at first, but a long red snake slithered out, testing the air, then retreated beneath the section of rock. The end of that snake reminded me of the forked tongue I’d seen in the cage this morning, as the rattler prepared to strike at my hand.

It was time to adjust my sense of proportion. Not a snake, but the outstretched tongue of a much larger lizard.

For a moment, we all played a panicked variation on cloud watching. The creature’s eye blinked, and I filtered natural crags and clefts from organic shadows, found patterns of chameleon scales amid the random bumps of the cliff’s weather-worn facade. Some of us perhaps saw a legless creature covered with bark, like a thick tree trunk battened to the side of the cliff. Some might have counted the sweep of eight thin legs as a hard-shelled spider scurried sideways across rough, perpendicular terrain. Eventually, for all of us, the image settled into a large four-legged lizard, spiny backed, with sharp talons digging into the rock as it moved.

We gasped at different times, as the approaching shape became clear to each of us. Saurus Stinkbugus. The hard scale armor on its back was the color and spiked texture of the carapace on a stink bug, on a much larger scale and with the addition of imposing reptile features. It was climbing headfirst down the cliff.

Jack rushed past our open-mouthed companions, almost pushed our tour guide aside, to scavenge the stored raft for potential weapons. He pulled each of the oars from their guideloops, handed one to Troy and kept the other for himself.

(Yes, Celia, I felt slightly insulted at the time. In hindsight I acknowledge our muscled guide would fare better with a blunt weapon.)

Jack found an emergency kit fastened beneath the raft’s control panel, and he unstrapped the plastic box and gave it to me. In addition to small bandages and single-use cleaning pads, I found a flare gun. But no ammunition.

“Oh, the flares got wet last season so I threw them out,” Troy explained. “Been meaning to replace them.”

The lizard moved lower on the cliff, passing the tops of nearby trees. Its spiny body became more clear in contrast to the rich, green leaves. I kept hoping it would eat part of a plant on the way down, reveal itself as a harmless herbivore, but the lizard’s appearance — the worst features of an iguana and an alligator, with the size and agility of a lion — suggested meat-eater all the way.

Kenneth moved ahead of his girlfriend as if he could protect her bare-handed. I wondered if her angry shouts had drawn the lizard to us, or if it had waited on the cliffside all along, still and invisible, planning to surprise oblivious victims.

“Why don’t we just go back in the water?” the woman said. The option seemed sensible, but I knew why it hadn’t occurred to Jack. He’d want to stand our ground, staying on the ground.

Which didn’t exactly move beneath us when the heavy lizard-weight dropped, but there was a definite crunch of twigs and thump against hard sand.

I’d been dreading the auditory confirmation. A stealthy predator would take pains not to announce its approach — but the same level of silence came from Jack’s typical hallucinations. Since a mental projection couldn’t harm us physically, I was still holding out hope that this was one of Jack’s visual-only glamours. The fact that others could see the lizard, too, made that hope unlikely — as did Jack’s own obvious fears, and his preparations for battle.

Then that confirming thump. An open, gator-mouth and that searching tongue. A snake hiss and a deep roar, and a pause that could only signal tension before a charge forward.

#

“Back between the trees,” Jack shouted. He and Troy acted as our first line of defense, raising their oars.

I dropped the useless Emergency Kit and did as I was told. Barb and Kenneth followed suit.

The plan seemed okay for us, since the trees were spaced too tight for the lizard’s gnashing head to fit through. Jack and Troy weren’t as protected. Our guide was muscular, and attractively shirtless, but he no longer seemed physically imposing as a giant lizard scampered toward him. For his part, Jack was tall and agile, brimming with confidence — but he didn’t have the practice, or the muscle tone, to back up his bluster.

I watched between two tree trunks. I watched between the fingers of hands held nervously over my eyes.

The only positive outcome I could imagine was a lingering, half-hearted wish that the dinosaur might still be a hallucination. A ghost image, dispersing through the air in the moment before physical contact.

Lizard feet stamped audibly through sand as the beast quickly crossed the small crescent of beach. As it got closer, the spine-scaled dinosaur seemed even larger, while Jack shrank to a spindly appetizer, our tour guide serving as the stocky, gristled entree. After the meal, the lizard could pick its teeth with the oars.

I felt helpless. Perhaps I should have grabbed a rock, made a prissy throw at the lizard then squealed as it bounced harmlessly off the hard-shell hide. Ken and Barb cowered behind a nearby pair of trees, similarly helpless. None of us had a plan.

And I feared Jack and Troy didn’t, either. I hadn’t overhead them whispering strategy to each other. They hadn’t, as the sportsmen say, called an audible at the last instant.

Jack and Troy clacked their oars together, as if to intimidate the rampaging beast. They formed a united front, their feet planted firm in the ground as they braced for impact.

They were just going to stand there and let the lizard choose its meal.

The dinosaur’s mouth opened wide, its sharp teeth gleaming wet, and it looked like it was going to swallow them both at once.

To be continued…

#

AUTHOR’S NOTE: ON DINOSAURS

I’d spent a couple of years away from this story, and one of the sections that surprised me on rereading was the over-the-top rant Barb delivers when her boyfriend tries to explain away the Pterodactyl. I think it’s my favorite moment in the whole story — a comical nod at that horror-movie trope when a character refuses to accept the supernatural, despite clear and present evidence.

The Pterodactyl is itself a nod to the first full-length dinosaur movie, 1925’s The Lost World, with stop-motion effects by Willis O’Brien (who later brought King Kong to life). When Professor Challenger and his crew reach a secluded island, the flying dinosaur is one of the first signs they’ve traveled to a world where prehistoric animals survived. Challenger points to a distant cliff, where a wire-suspended model glides overhead: “A Pterodactyl –– proving definitely that the statements in poor Maple White’s diary are true!”

There are better moments to follow: an Allosaurus attacking their camp at night, a dinosaur stampede, and a Brontosaurus brought back to London where it escapes and terrorizes the city (as a giant ape will terrorize New York City eight years later). My younger self grew fascinated with movie-magic dinosaurs, particularly the stop-motion kind, which had a strobing unreal movement that enhanced their fantastical impact. If a movie promised dinosaurs, I’d happily sit through an hour of tedious build-up until the big lizards showed up (as long as they weren’t actual lizards with fins pasted on their backs. I’ll never forgive an episode of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea where Admiral Nelson points to a stock footage iguana and said, “There’s a Stegosaurus.” Uh, nope.)

The raft journey in this story might be an unconscious tribute to a Saturday morning show from my childhood, Land of the Lost, where a ranger and his two kids tumble over a waterfall into dinosaur land. They went over that waterfall each week in the show’s credits.

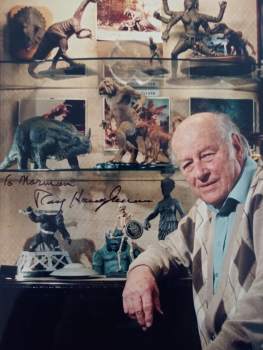

But the best dinosaurs in my youth, and arguably unequalled to this day, were animated by Ray Harryhausen in One Million Years B.C. and The Valley of Gwangi. I’d be glued to the set whenever these films were scheduled, and I knew when each of the stop-motions creatures were scheduled to arrive. In those days before VHS or DVD or on-demand streaming, you could order edited Super 8 versions of some films that you’d thread through a home projector, and I’d purchase any Harryhausen 12-minute reels my small allowance could afford. In addition, there was an unadvertised loophole at local theaters: although you couldn’t move from one film to another at a twin-screen movie house, they would let you stay to watch the same film again. So when a dinosaur or Sinbad film was on revival, I’d have Dad drop  me off for the afternoon. I saw Gwangi twice; my record was 7th Voyage of Sinbad, which I saw three times in a row for two consecutive weekends (no dinosaurs, but a cool dragon, and a memorable Cyclops).

me off for the afternoon. I saw Gwangi twice; my record was 7th Voyage of Sinbad, which I saw three times in a row for two consecutive weekends (no dinosaurs, but a cool dragon, and a memorable Cyclops).

As a writer, and a fan of writers, I’ve been very lucky to work with some of my favorite authors while at Cemetery Dance, and to meet them at conventions. But of all the autographs I’ve ever gotten, I think the most important to me is from a FANEX “Monster Rally” convention in 1999: the attached photo of Ray Harryhausen posing in front of a display case of various creatures from his movies –– signed “To Norman” above a Kong model, and beneath the Styracosaurus from Gwangi.