“Horror and weird fiction is the labyrinth.”

Night Time Logic is the part of a story that is felt but not consciously processed.

In this column, which shares a name with my New York based reading and discussion series, I explore the phenomenon of Night Time Logic and other aspects of horror fiction by diving deep into the stories from award winning authors to emerging new voices.

I have an interest in strange tales, the kind of story one might call “Aickman-esqe” and like to discuss them here and look at stories through that lens when I can. My first short story collection is titled The Night Marchers and Other Strange Tales in homage to the lineage of Robert Aickman’s strange tales. The new Cemetery Dance Publications trade paper back edition of the book can be found here. It discusses strange tales in the all-new story notes and features a full essay on one of Aickman’s tales.

In my previous column I spoke with Ray Cluely about ghost stories, settings in his fiction, his strange tales and more. In today’s column I speak with Justin Burnett about “leaving knots tied,” the uncanny, doppelgangers, music, labyrinths and more.

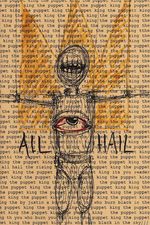

We begin with a discussion about his debut fiction collection The Puppet King and Other Atonements.

#

DANIEL BRAUM: The name of the book is The Puppet King and other Atonements. A definition of “atonement” is “to suffer the penalty for sins, thereby removing the effects of the sin from the sinner and allowing him to be reconciled with god.” Another definition I read is “atonement is the process by which people remove obstacles to their reconciliation with god.”

DANIEL BRAUM: The name of the book is The Puppet King and other Atonements. A definition of “atonement” is “to suffer the penalty for sins, thereby removing the effects of the sin from the sinner and allowing him to be reconciled with god.” Another definition I read is “atonement is the process by which people remove obstacles to their reconciliation with god.”

Whether used as per its official definition, “atonement” is a word with religious connotations. Are these religious stories? Why did you choose “and other atonements” to be in the title of the book?

JUSTIN BURNETT: At the time of writing them, I can’t deny that I thought of the stories as religious, at least in a loose sense. Now I’m a little more wary of the connotations dredged up by the word “religious” — numinous might work better, or something else entirely — but I’ve long felt that horror fiction exploits the same disjunction between the self and the universe that religion does.

One reason this has been particularly clear to me is that my earliest experience of cosmic horror was a sermon on the Revelation of John. The sanctuary was lit with candlelight for the occasion, and the description of multi-headed, many-eyed monstrosities moved me vividly. The depiction of Hell in Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is a good approximation to what I was subjected to regularly throughout my strict Southern Baptist upbringing. When I finally discovered horror, the territory struck me as darkly familiar.

“Atonement” for me is “at-one-ment.” At one with what? With the inherent emptiness of human existence. With nothingness. With death. With the reality of these things and the impossible imperative to somehow survive them. I’ve gotten a few sideways glances for claiming the stories here were urgent to me, but they were utterly real insofar as they sought atonement with this incomprehensible reality. It might be better to call them therapeutic, or cathartic — whatever they were, they felt religious at the time, particularly if I could be permitted to suggest that the religious impulse is one of mystification rather than explanation.

Ten out of the fourteen stories in the book are original to the volume. The first of these original stories and the first story in the book is “The Toy Shop.” In the story there are dolls (while not actual puppets perhaps they are similar or close), there is a character with a philosophical world view (who mentions Rilke), and there is an unexplained “happening” unfolding at the same time as the story of the narrator, a woman we know as Braxon’s mother. For those yet un-initiated to your work, as I was when I read this story, can this story and these elements be taken as a key or guide on how to read the book and the stories to come?

I hadn’t consciously thought of “The Toy Shop” as a guide, but I think it could be. There are two registers at play: the cosmic, and the inanimate (the latter what Tadeusz Kantor would call “Reality of the Lowest Rank”… I prefer “Reality of the Lowest Order”). I attempt to oscillate between these registers, because I think that something connects them. In my mind, while writing this book, I was endlessly climbing the puppet’s strings to the stars or sliding back down them again into some faceless object. In lieu of an extensive digression here, I’d say we’re all aware that our all our gods were first puppets (literally, in the form of physical idols) and through them humanity gained imaginal access to the cosmos. Utilizing this primal link in fiction is an interesting challenge, one I can’t resist teasing just a bit.

“The Toy Shop” should also make clear that I tend to leave knots tied. This is a matter of preference — I’d rather preserve a scene or gesture than dissolve one by the process explanation (mystification again, perhaps another impulse somehow related to religion). And there’s the first instance of depression and suicide, two very prominent themes throughout the remainder of the book. I’d say that a reader could fairly gauge their potential enjoyment of the collection based on “The Toy Shop.”

I took great interest in the event in the story, the event referred to as “the supernova” and how it was presented. While still a force in the story the specifics of what was actually going on were not given and it remained unexplained. Thus, with the focus off the mechanics and particulars of this happening the internal stakes and emotional realities of the character took center stage. In this way, the story operated for me similarly to the way I perceive Robert Aickman’s strange tales. Tell us about the decision of presenting the element “the supernova” as something unexplained.

The supernova was an image that surfaced after “The Toy Shop” was well underway. Initially, an outline for a separate story accumulated around it. But then I took the advice of Jeff VanderMeer in Wonderbook. It went something like — I’m paraphrasing here, perhaps badly — don’t save your best ideas for later. Let your brain go wild straight away. So, in goes the supernova, and I felt like it worked.

It’s important for me to leave things unexplained, particularly eruptions or visitations of cosmic weirdness, because when something close to these visitations occur in real life — in the form of mystical experiences, abduction phenomena, or all the smaller, easily forgotten events that challenge our notions of causal order — they lack explanatory devices themselves. You could say I’m striving for a certain level of [ir]realism. I want these elements to remain irreducible because that’s the whole point, as I see it, handing the reader something irreducible, a mental event that is mine alone but objectified so that it can be shared. If it looks something like a puzzle, it’s because it’s still mine, still connected umbilically to its deep origin. If it were otherwise, it would lose its object-nature. It can’t be a puzzle, no more than a labyrinth seen from above is able to maintain its mystery.

I don’t mean to make my creative process seem as occult or complicated as I’ve probably made it sound. Other writers have pointed to this element of irreducibility — right now I’m particularly reminded of the poet Federico Garcia Lorca and his “Deep Song,” which influenced Roberto Bolano; I consider both among my favorite writers. All this may just be a circuitous way of saying some of what bubbles to the surface is better served plain.

In the second story, “Sister” we have the appearance of an actual puppet. Tell us about the puppet in this story. Tell us about how you use doppelgangers or doubles, both in this story and in the book as a whole.

There’s this nexus of images associated with labyrinths. Among them are mirrors, blindness, doubles, webs, puppets, and caves. This probably has to do with Freud’s famous discussion of “the uncanny,” which began the work of formal lashing these slippery and highly subjective images together. But these associations are not academic. In novel after novel these themes appear in organic clusters, especially when the novel in question has anything to do with labyrinths (and many novels do, since labyrinths are also texts. Consider the origin of the word “text” — Latin textus, meaning “thing woven… to weave, to join, fit together, braid, interweave, construct, fabricate, build” [from Etymonline.com]). Last year I read Italo Calvino’s Hopscotch, and I was struck by the perfect clarity in which this association of images surfaced in one of the book’s final and most important chapters. Nabokov is directly relevant to this discussion too.

But to return to your question, I feel less like I “use” doppelgangers and more like they form one of several focal points liming a central image, much like the stations of the cross. Yes, there’s the uncanny element, which is clearly useful in horror, but no explanation of “the uncanny” feels satisfying to me (Freud’s least of all). I find myself rather in awe before the power of this image rather than an adept manipulator of it.

This element of passive fascination is even more relevant to the puppet scene. It was first a dream that I recorded several years before writing “Sister.” I tried and tried to write a story around it, but I couldn’t find a way to frame it. The vast stage with the looming figure in the background was like a black hole — it swallowed everything I put near it, so I left it to tug at the back of my mind for a while, until, like the supernova in “The Toy Shop,” I found a way to splice it into what was well on the way to becoming “Sister.”

If there’s one way to answer the question of “use” of images in the collection, it’s this: while writing many of the later stories of The Puppet King, I had the image of the Puppet King Itself consistently in mind. It was a stable entity: a massive puppet with a labyrinth carved into its flesh, with mirrors for eyes, so that anyone who approaches can see that It is their twin, that It echoes the vast emptiness inside of them.

Music and the supernatural play a large role in the third story, “devourer”. There is something about the connection between music and the otherworldly and the unknowable that has made it a find its way into the stories of many authors of the strange, weird, and cosmic both contemporary and in history.

Two stories from Lucius Shepard, one of my favorite authors, come to mind when thinking of the pairing of music and the cosmic and weird; the novella “Stars Seen Through Stone” and “Skull City” come to mind. I think there are as many unique takes and iterations on this topic as there are authors, each which their own unique musical interests and connections to the music. This is what keeps this variety of story feeling interesting and new to me.

Please tell us about you musical interests. What bands or kinds of music inspire you and this story? How is music used in “devourer” to connect with the cosmic?

I haven’t read anything by Lucius Shepard (I’ll have to change that), but I agree that music in weird fiction is always interesting.

I got into metal early on. After finding a Deftones album in my collection, my parents only allowed me to buy CDs from Mardel Christian & Education through my earlier teens. Thankfully, Christian metal and hardcore was gaining popularity, so I survived on that until their divorce presented my parents with bigger problems. Like most metalheads, I eventually moved on to explore other genres — a maturation partially reflected in “Devourer.” Like Ulver, Kayo Dot, and other metal bands, Devourer wants to transcend the genre’s limitations. The attempt takes him several steps farther than that, of course.

Perhaps it’s the fact that music let me escape the narrow Southern Baptist landscape I was born in that gives it the appearance of a natural medium of communion between different states of reality. What else but music — this intangible but real and deeply affecting phenomenon — could reach across barriers of language into some otherwise inaccessible dimension? More important, however, is the fact of music’s immanence, its irreducibility. It’s a mystery that develops right here, and transportation in real time into what is at once a universal and highly subjective experience.

I’ve mentioned “irreducibility” again — I just want to note that it’s not a term I’ve tended to use in the past when thinking about fiction. I have no true stakes in it. It’s very possible that I would explain this in completely different terms on any other day, and it’s certainly not what I had in mind when writing these stories.

It’s probably more realistic to say that, as in most cases, the decision to use music to connect to the cosmic in “devourer” simply felt right at the time. Books, more than music itself, had put me in the mood for the experiment. I think I had recently read David Peak’s Corpsepaint, and I had certainly been skimming AUDINT-Unsound: Undead, an anthology on music, to quote the Amazon description, that explores “…the potential of sound, infrasound, and ultrasound to access anomalous zones of transmission between the realms of the living and the dead.” The latter — featuring contributions from academic writers like Eugene Thacker as well as musicians, including Tim Hecker, a favorite of mine — sits woefully underexplored in the Kindle library. I’m glad you reminded me of it.

A follow up on “devourer.” I enjoy how what the character named Devourer is doing with the music is “intentionally ambiguous” and thus the story operates as a strange tale for me.

Whether there was in fact something super-natural in play or if what is happening is a perception or desire of the characters is not definitive, in my opinion. Tell me about your decision to leave this unexplained.

I forget who says it — perhaps Joel Lane? — but somewhere, I read that good weird fiction narratives effectively teeter on the balance between causal explanation and insane delusion. (I get the feeling that Lane brings this up in connection with another critic, someone working in fantasy. At any rate, I think more people should read both Lane’s fiction and nonfiction.) I consciously tried to do that in “devourer” since I had just come across the above-cited and subsequently forgotten passage, and it hit me like a revelation. (Now I’m beginning to think this is Mark Fisher in The Weird and the Eerie, not Joel Lane at all. Maybe it’s both.)

I think about this less now. I’ve come to accept that I don’t even know what’s real or delusion in my stories, and that trying to insist one way or the other would be disingenuous. This outlook has proven something of a relief.

Are the story titles in lower case a visual style choice of the publisher or something otherwise?

It was a mutual decision between myself and the publisher, intended to match as closely as possible the typeface on the cover. When designing Hymns of Abomination: Secret Songs of Leeds, Silent Motorist Media’s tribute anthology to Matthew M. Bartlett, I used the lowercase typeface and liked it. It’s much closer to an aesthetic impulse than anything else.

Here is an excerpt from the next story “the rubber man.”

If she subtracts the desires of others and follows the unnamable impulse that feels much closer to an identity than her assigned roles as project manager and partner, she’d find herself right where she is now, on Icarus Island. For once- storm and sun and the overwhelming smell of fish non-withstanding- she feels more human than puppet.

Tell us about the setting of Icarus Island in the story. Is there a connection to the Icarus of Greek myth, Icarus son of Daedalus, who created the labyrinth of Crete?

I wrote this one after a spring break with the wife and kids in Rockport, Texas. We got there late in the evening, and after checking in to our run-down but conveniently located motel, we walked out onto a pier. It was dark, and enormous cockroaches and silverfish scuttled out of the rocks surrounding the concrete and into the moonlight. The Gulf captivated me, as it always does (something about the smell of the ocean, the limitless expanse — I’m reminded of the chapter “Loomings” in Moby Dick) and it was inevitable that a story would come out of it.

Icarus island is imaginary, but yes, it has everything to do with Daedalus’ son, who attempts to escape the Minoan labyrinth with wings made by his father. He fails of course — ends up flying too close to the sun — but, if only for a moment, Icarus sees the labyrinth from above, a rare perspective that signifies a renewed relationship to the maze.

In certain moods, I share the medieval Christian conception of life as a labyrinth. We’re trapped by our own concepts rather than by our sins, however, and to see the maze from above would be to transcend it. But such a vision would come at a price. I imagine Icarus’ features blanched by the sun, his eyes sightless. This is the mode of transcendence that one would describe as annihilating, a kind of madness suitable for the Lovecraftian dimensions of this story.

I have to admit, this way of looking at the numinous has become less interesting to me lately than the possibilities afforded by allowing oneself to get lost in the maze, but that’s another discussion entirely.

“There is no destiny. Beauty, perhaps, but not destiny.”

This line appears near the end of the “the rubber man.” Please tell us about this line.

“Beauty” is a strange concept given the circumstances the protagonist finds herself in at the end of the story, but it’s beauty she should’ve been looking for, not answers (i.e., “destiny”). She’s punished for realizing this distinction too late, just as we often are. This sounds close to moralizing, I’m afraid.

The point is that Kaire experiences something unexplainable (UFO abduction) and assumes that it must mean something. It’s particularly difficult to avoid doing this when faced with the unknown, since the imposition of meaning is an attempt to exert control on a chaotic scenario. In the story, the presence of the rubber man in her life is just that — a presence. There is nothing else. Insisting on destiny turns out to be incredibly dangerous for her. I think it’s equally so for any of us.

What the hell, I’ll go ahead and moralize here: on the macro-level, “destiny” is the kind of imposition of form that gives rise to institutions that believe in some transcendent imperative to destroy what opposes them. On a personal level, it gives us permission to accept what we shouldn’t accept, or to demand what we have no given right to demand. This often makes for serious suffering, individually and globally.

The story “endemic” has an aspect of science as its central premise so I can see classifying it, if one was looking to do such a thing, as science fiction perhaps. For you, how does the story differ from the set of stories in the book? How is it similar?

Each story feels unique in terms of method and inspiration, but you’re right to single this one out, I think. Several elements make it distinct. This was the first story that I wrote and looked back on with the feeling that I knew — at least somewhat — what I was doing. I was reading Christopher Slatsky’s The Immeasurable Corpse of Nature and thought aha, this is how it’s done. There was an element of immersion, of seemingly inconsequential detail (but not too much) that I felt my writing had been missing and which I tried to incorporate into “endemic.”

There’s also the fact that “endemic” was a half-finished screenplay before it was a story. Since childhood I’ve been fascinated with caves, and when I read about endemism and Movile cave (mentioned in the story), my head exploded. Immediately, I went to work on the screenplay, which eventually turned into the story.

There’s not a lot of the Puppet King in this one, but It’s there in spirit, in the emptiness of the panhandle landscape and the deterioration of reality surrounding an eruption of the unexplainable.

Other readers have also described my stories as science fiction, and it probably shouldn’t surprise me. Another major inspiration throughout is J.G. Ballard — that enormous Norton volume of collected short fiction of his is a perpetual delight. It never makes it too far from nightstand.

Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Hell is Other People” is mentioned in the story “m.other”. Philosophy and references to philosophers and authors are a recurring presence in these stories.

How does the Sartre quote operate in “m.other”? Tell us about your process to include it and other quotes and references in your stories?

While I haven’t personally gotten much mileage out of Sartre’s brand of existentialism, I like his fiction. At the time of writing this one (2016 or so), I must’ve been reading his plays. “The Flies” is a favorite of mine, but I believe the quote comes from “No Exit.” In the context of this story, the quote describes a scene quite literally — the street sign with the word “Hell,” and the mass of people other than oneself (mass other = m.Other)…. The irony here is that the protagonist has been creating his own hell without their help.

If there’s one thing I know more than anything, it’s books. Everything I write and think is in conversation with something I’ve read, and I see no reason to pretend that this relationship doesn’t exist. If a work is tied to a book I’m reading, and if it fits the story’s universe, I include a direct reference. I think of them as “further reading” suggestions, and I know I appreciate them in books I read. There are even some books — Roberto Bolano’s 2666 comes to mind — that I essentially approach as massive reading lists. I admire how Bolano’s work is nearly always about reading just as much as it’s about anything else.

Tell us about the self-referential elements in “m.other.” Are they or any other elements meant as a cue to read anything as an author surrogate?

Every character, to some extent, is an author surrogate, but I feel that this is least the case with the protagonist here. This is the oldest piece in this collection, and I was still writing with far more didacticism than I’d use now. I thought it was a story’s job to punish a bad guy, I had been reading Lacan, and so the two elements became this unethical Lacanian psychoanalyst. Looking back, I’m glad I stopped believing that stories need to operate in this way.

In the story “the enucleator” the characters encounter another labyrinth, of sorts. Can you tell us about how digital and technological elements come into play in your stories? And the recurrence of labyrinths in your work. Where did your interest in labyrinths originate and develop?

Technology poses an interesting challenge for contemporary fiction. I tend to be one of those who imagines all sorts of problems arising from our collective addiction to social media and the various low-level hamster wheels of online entertainment. On the other hand, I’m aware that my skepticism certainly isn’t going to make any of it go away. Since fiction is inevitably subject to the new perspectives and modes of distribution presented by technology, this relationship is worth careful attention.

My literary introduction to labyrinths was by way of Jorge Luis Borges, who I still return to frequently. Before him — even in early childhood, before books were important — I had always been fascinated by labyrinthine spaces. Caves (particularly Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico), the network of small creek beds that ran through the woods on the property I grew up on, the tangle of overpasses where the loop crossed the interstate on the way to Ft. Worth that I found so horrifying… I used to fill stacks of paper with drawings of ant formicaries, tunnels branching to various chambers, each with a specific function and human furnishings. These spaces held my mind captive and I’m not sure why. Maybe it was that I visited them in dreams as well, vast cities lit with dull green lights, tunnels sloping deep into the Earth…. Remembering this, I’m suddenly aware that I always had an impulse to hide. I always felt safer in the dank darkness of a cave.

Later, during a horrible year in college that ended in institutionalization, I read most of Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves. I would never fully get that book out of my head, even though I’ve been far less impressed with it in later years. I think it forged the nexus of labyrinths and horror that I’m still playing with in my fiction.

I realize there’s no firm why in there. I’m afraid a satisfactory why may not exist. There’s just an abiding interest and the pleasure of rolling it over in my head.

L’appel du vide is French for the term “The call of the void” which I will briefly summarize as the human compulsion for self-destruction.

In “the golden thread” the narrator says: “I realize now that it wasn’t a fear of falling that kept me huddled in the backseat of the family van. It was a mistrust of my own will, the inexplicable draw to the edge that I realized I was inclined to obey. Imagine that, if you can: annihilation resounding in your cells…”

How did you dramatize and put into dramatic structure the concept of L’appel du vide in the story “the golden thread”?

Sometimes, I like to think of events in a horror story as holes. As holes in what? In the structure of our socially constructed reality, this thoroughly human world we simultaneously dream and inhabit, which entails all the structures on which we depend, language, order, law — in short, as the sociologists handily call it, the nomos. A hole in the nomos would be any event that forms a rupture in the surface of socially constructed reality that exposes what the world of human consciousness can’t manage to fully paper over (see in this connection Terror Management Theory as proposed by Jeff Greenberg, Sheldon Solomon, and Tom Pyszczynksi in The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life). While these holes are connected to experiences like death, revolution, and insanity, the substance of the hole isn’t simply these experiences. In fact, the hole is nothing we can name. Even “death” doesn’t fully do the trick, since “death,” with its standardized stages of grief, its funerary rituals, its insurance coverage, is securely embedded in the nomos. There are two deaths: death within the structure of society, and death as an inconceivable condition that threatens to overturn the whole structure of human reality (threatens it and forms its basis simultaneously… See Julia Kristeva in Powers of Horror). What’s beneath is the remainder, the irreducible, or as Eugene Thacker likes to call it, the nonhuman.

So these holes act very much like actual holes, which are also drains. They draw the attention, they form the center of a spiraling movement — they are abysses into which we are nudged, not by an external force, but by our own curiosity regarding what lies beyond the sober structures of our world. I’m reminded of Philip Fracassi’s Altar, only the call emanates from within the individual — the hole and the beast at the bottom are simply facts, indifferent.

In this sense, I think L’appel du vide not only works within the structure of a horror story but is a description of the structure itself. I particularly like the French formulation because it is often associated with heights. I’m deathly afraid of heights. I have a set of mantras I say while driving over even modest bridges. I refuse to fly. The passage you quoted above is directly autobiographical. I really did hide in my grandparent’s van on a trip to the Grand Canyon. It really is a mistrust of my own will, a nagging compulsion to leap that keeps me away from edges.

“the golden thread” might be the quintessential Justin Burnett story. We have time-displacement as a labyrinth. Science. Technology. Philosophy and literature.

As you do with other stories in the book, “the golden thread” is told by presenting one part of a dialog only.

Is this a story about a mundane orientation to a mundane job or is it an anecdote about notions of God? Is it a tale of the mundane or a tale of humankind’s struggle with the notion of and meaning of existence? Or both?

I like the idea of this one being representative of my stories. I think, if I were to point to anything in particular that “The Golden Thread” is about, I’d say it’s the way that truly holy things tend to be an absence rather than a presence. But I’ve already touched on that a bit in the preceding answer.

One thing I’ve noticed is that deep down people can’t stand the quiet. Something in the stillness unsettles them. It poses a challenge and the things that rise to meet it are the very things people wish to hide.

This passage from “a prisoners guide to stargazing” is one of the narrator’s many ruminations on what it means to be human.

How do science fiction stories, stories of the cosmic, and stories of aliens lend themselves illuminating the human condition? What about Texas and Texans do you want readers to come away from the book with?

On one level, “the human condition” isn’t really something I set out to capture or comment on, at least not in a general way. However, I think that extreme circumstances — events, horrific encounters, glimpses of things you don’t come across every day — are more convincing when they cause a character to reflect on the state of things around them. One can’t be plucked out of the seamless functioning of the social world without being altered by the sudden realization that things were essentially other than what you previously assumed them to be (we can call this the viewpoint of Icarus, to return to the labyrinth myth). If anything brings up the question of “the human condition,” it’s these extremes. Writing these observations then is just an attempt at realism.

And yet…

The quote you mention isn’t really a new, world-shattering observation. Many people openly admit to not being comfortable in silence. It’s strange. We live in a whole world of extreme events — genocide, death, pain, suffering — and all we can manage are reformulated versions of the same old “truths.” If extremes bring questions of “the human condition” into focus, it’s still the same old condition. I think there’s a reason that extreme sufferings tend to reorient people around the “small things” in life.

I’m emphasizing this to somewhat deflate the seemingly lofty vantagepoint of Icarus. This talk about suffering positing privileged perspectives may smack of transcendence. I don’t want to pander to transcendence. Neither, truly, does the myth — the only transcendence Icarus finds is death.

To answer the part about Texas and Texans, I don’t really have much to say about either other than this is where I’ve been and these are some of the people I’ve been there with. I’m not sure how Texans compare to others, since I’ve spent my whole life here. Texas is simply what I know, for better or worse.

“our endeavors” is one of several stories in the book told via a unique view point and a unique delivery of the narrative. Were the stories written in a sequence or were they assembled and sequenced after completion? Were the viewpoints taken into account during the sequencing and or drafting of the stories?

They were sequenced after completion. In each of them, the narrator is a character within the story. At the time, I couldn’t accept the narrator’s perspective as simply given. It’s not that I minded reading stories told from the mysterious third person omniscient, but I couldn’t write them. I tried. If I were tempted to introduce an omniscient narrator, I felt like there needed to be a reason for their omniscience. That’s exactly how the narrator of “our endeavors” came about. “ABDN-1” features a similarly omniscient narrator, as does “the enucleator.” “the rubber man” acts like a third person omniscient but turns out to be first person all along. In short, I didn’t want my pickiness about narration to saddle me with a fist person point of view all the way through the collection. That’s where the experimentation in point of view comes from. I took each story’s existence as a story as a problem to be solved, even the ones (namely, first person) that feel more traditional, so I couldn’t say the odd points of view came from a sequence distinct from the rest of the writing of this book.

For the record, I don’t want this to seem like I look down my nose at stories that don’t worry too much about the problem of narration. I’m not against writing from an ambiguous third person point of view. I’ve done it myself a few times since writing these stories, and I think leaving the question of who is telling the story wide open can be a perfectly satisfying compositional choice.

…you have been wrested from the restless delusion of living, the constant need to perform your puppetry.

Is the narrative and narrative a misdirection because of what is revealed in the end of the story? How is the story another exploration of the notion of the puppet?

I try to work an element of misdirection into each narrative. I appreciate a horror story (or any story, really) that tilts the world it establishes to such a degree that you’re not exactly sure the world it ends in is the same in which it began. There’s definitely an element of that in “our endeavors.” Or so I hope.

The puppet line points forward to the final monologue, where much clamor is made about life as a puppet play which can only be worn seamlessly if it is apprehended in its full emptiness and willed to be so, a sort of proto-Buddhist intuition of sunyata that ironically paved the way for my subsequent exploration of Buddhism directly following the publication of this book.

I thought — still think — that thinking deeply about puppets is just another way of thinking about life. The puppet is wonderfully liminal, an object lodged between the inanimate and living world (Bruno Schulz’s treatises on mannequins cracked my brain wide open, irreparably), but also between debasement and divinity. And yet they are, what, mindless bits of wood? porcelain, plastic? nothing, a fold in the fabric of what is at once nothingness and everything. People familiar with Zen will feel an affinity to this description, although it adopts a much darker façade in this book.

The “subject” in this story is a puppet insofar as the tragedy he experiences empties his life of meaning. He’s a puppet insofar as his response follows a perfectly predictable trajectory. He’s a puppet in the hands of the manipulative narrator, who is a puppet of the hive in turn, and it isn’t revealed what forces the hive is puppet to, but one gets the dizzying notion it’s puppets all the way down, including the author and beyond, existence couched in increasingly occult forces that we can’t even imagine. And each level of subjugation is empty, a register that is incomplete in itself, just one way of looking at things, but by no means essential. In this infinite regress of emptiness, there is no substantial difference between one emptiness and another. One’s personal puppetry is sufficient to apprehend the puppetry of the universe. And if emptiness is the only thing that ties one register to the next, then emptiness is what is.

Only it’s not so bleak. Buddhism, again, addresses this exact perspective. Maybe I felt this on some level, since I kept thinking about how the viewpoint of the living puppet underlying the book was essentially the only positive response one could formulate against the horrors depicted here.

Labyrinths and puppets and those who write about them are an inspiration to you and recur in the stories. Tell us about these inspirations. Who are the writers and philosophers that inspire you and why? How long have they inspired you? Where do you see yourself in connection to them and their work?

I’m a latecomer to horror and weird fiction. I read Mark Z. Danielewski, as I’ve mentioned, early in college, but that was the end of my exposure to horror for a while. Preceding Hose of Laves, my exposure to labyrinths was by way of Borges, who I’ve also already mentioned. There was also Kafka, who, along with Samuel Beckett, formed what I might call my “first wave” of influences — writers who evoked strange, uncanny, and labyrinthine worlds I found deeply fascinating.

I also came across Freud in college, which was probably my gateway into thinking about the uncanny as an aesthetic problem. Aesthetics fascinated me, because I felt that it was impossible to quantify the experience of art, and reading the history of aesthetics seemed to reenact this impossibility because elements like the uncanny and the abject were always there to antagonize comprehensive statements about beauty. This is still an issue I work with in my writing, and it’s led me across a wide array of essays and books that tend to get lumped into the categories of philosophy and theory.

Later, after fully “discovering” weird fiction and cosmic horror with Matthew M. Bartlett’s Gateways to Abomination and Philip Fracassi’s Altar (this would’ve been right around 2015-16, the tail end of my college years), I quickly came to Ligotti, then Lovecraft (I know — backwards, right?) then the lesser-known Bruno Schulz. I’d say Ligotti and Schulz are by far my biggest influences. I’m constantly re-reading them. I feel entirely at home with them, particularly in the case of Schulz as of late, although I certainly favored Ligotti during the writing of The Puppet King. I seem to feel the pull of Lovecraft less and less, although I can’t deny his impact.

The pessimists loom large here: Ligotti, Cioran, Eugene Thacker’s Horror of Philosophy trilogy, Fernando Pessoa in The Book of Disquiet, Schopenhauer, Mark Fisher… there are more, I’m sure. While I wouldn’t exactly call myself a pessimist anymore, these writers absolutely shifted my landscape in a way that made it easy to see where cosmic horror came from, how to write on its wavelength.

There’s also William Hope Hodgson. I’d say I enjoy Hodgson way more than Lovecraft. J.K Huysmans turned my reading world upside down at some point, as did Robert W. Chambers.

Most important, however, are the contemporary writers I sometimes have the honor of knowing online. Brian Evenson, Michael Cisco, Kaitlin Kiernan, Gemma Files, Matthew M. Bartlett, Philip Fracassi, Laird Barron and many, many others. I try to keep track of them when I’m not entirely lost down some reading rabbit hole (as I very often am). I buy everything that Jon Padgett publishes over at Grimscribe Press. I try to read every story in Vastarien.

But now I’ve gone on and on without answering the last part of your question. I’m still very new to horror and weird fiction, and I’m not sure at all where I fit within it. Above all, I see myself as a fan of books. I try to respond to the books I enjoy with books of my own. I try to write what I’d like to read. I can’t claim a deeper relationship to the writers I admire than that.

In reply, I don’t think your path is backwards at all. We all have our own paths. I’m a late comer and a relative new comer to horror and weird fiction. And I am woe-fully under read in these genres. There is no one way or one path — just the one’s we’ve found and made for ourselves.

How do your inspirations of labyrinths and puppets relate to and intersect with notions of horror and weird fiction both contemporary and otherwise?

This is a great place to point out that I see a growing fascination with spatial elements in horror and weird fiction. As communal spaces become increasingly anonymous, as spaces we once knew become eerily empty, or replaced by spaces that are more virtual, less stable, more prone to deterioration and alteration, I think this spatial fascination will continue to gain ground.

Several years ago, I took my kids to a mall I had enjoyed myself as a child. To our mutual surprise, it was empty. We walked down long corridors of abandoned shops and branching unlit hallways until we came to a playscape erected in a corner of the bottom level. Apparently, the mall — once an endless drone of activity, as I explained to the kids, who seemed to hardly believe me — was kept open solely to accommodate this playscape and a single toy store. I didn’t know it at the time, but this was an instance of the “dead mall” phenomenon that only gained ground with the pandemic. This was before I had happened across vaporwave and its relevant subgenre, mallsoft — before I had come across the Backrooms and liminal space.

There’s something vaguely carnivorous about these commercial nonspaces, isn’t there? Like a dark hole in the forest, black windows of a derelict storefront awaken an instinctual aversion. Bad things are in there, you feel, but what? Something must be inside, even if it is emptiness, and since we’re programmed to read buildings like faces, what stares back at us is the uncannily hollow eyes of the puppet. When a space is reclaimed from human utility, it changes. It’s entrances and exits are blocked to prevent the flow of traffic, a removal from the everyday logic of transaction upon which our world depends. In removing its entrances and exits, a space loses its purpose. It becomes a meaningless loop, a labyrinth, an abomination too close for comfort to its subterranean analogue, Hell.

This is but the latest inflection of horror’s association with Hell. There’s good reason that right at the inception of horror, we find a house: Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto, the castle in Beckford’s Vathek, and, preceding both, Piranesi’s Carceri. Who can know why gothic spaces began to inspire fascination right at the inception of the Enlightenment. I, for one, am inclined to think it had something to do with people tracing the presence of the otherworldly back to those timeless intersections between the divine and the human: caves.

Horror and weird fiction, in short, is the labyrinth. Monsters are just personifications of so many secular iterations of Hell. I’ve filled several notebooks with notes on horror films and video games with this theme in mind. I only grow more convinced.

#

Justin A. Burnett is the author of The Puppet King and Other Atonements. He’s also the Executive Editor of Silent Motorist Media, a weird fiction publisher responsible for the creation of the anthologies Mannequin: Tales of Wood Made Flesh, which was named best multi-author anthology of 2019 by Rue Morgue magazine; The Nightside Codex; and Hymns of Abomination, a tribute to the work of Matthew M. Bartlett. He’s currently writing a novel while living in Austin, Texas, with his partner and children.

#

Daniel Braum writes “strange tales” in the tradition of Robert Aickman. His stories, set in locations around the globe, explore the tension between the psychological and supernatural.

The all-new Cemetery Dance Publications edition of his first short story collection The Night Marchers and Other Strange Tales can be found here.

Cemetery Dance Publications will be releasing his novella The Serpent’s Shadow in Fall 2023.

Braum is the editor of the Spirits Unwrapped anthology, the host of the Night Time Logic series and the annual New York Ghost Story Festival. Find him on his You Tube channel DanielBraum, on social media, and at bloodandstardust.wordpress.com.